We listen to a lot of classical music when we’re testing hi-fi and headphones. Perhaps not as much as our high-expectations parents or old music teachers would ideally like, but stick a glass to the door of our test room(s) and you’ll hear plenty of Delibes, Beethoven and Brubeck flowing melodiously from our listening chamber. We have also heard all the Hans Zimmer and John Williams that there is to hear, but let’s not get into the thorny issue of whether modern film scores should be considered “classical” music. Classic FM plays a lot of movie soundtracks, that’s all I’m saying.

The real marvel of classical music is that it’s such a nebulous term. Classical is generally used for anything that’s non-electronic, incorporates traditional instrumentation and was composed before the 20th century by portly German gents in funny wigs and large hands; but if you’re going on those criteria, you’re missing out on great swathes of music that very much fits the bill. When you consider that the true “Classical” period only lasted from around 1750-1820 and that the earliest Medieval works that one would still file under the classical banner date back to around the 11th century, you start to realise that it’s a pretty broad church, and that’s before we’ve expanded the search to include pre-classical works such as the Seikilos Epitaph from Ancient Greece or contemporary composers such as Arvo Pärt or Max Richter.

So there’s a lot of great music out there to give the process of testing your speakers a touch of class. Why, then, have I singled out a Frenchman with an oft-mocked surname and a silly little goatee beard as being my absolute favourite composer when it comes to producing some of the finest classical test compositions for your hi-fi, headphones and just about anything else besides? Despite his pre-eminence as a giant of Late-Romantic composition, few academics or experts would put him up for a candidate as the greatest of all time. Bach, Mozart and Beethoven make up the usual triumvirate of greats, usually in that order, so what’s so special about dear old Claude?

It’s a question that you could ask about almost any great musical maestro, from Hildegard of Bingen to Edward Elgar and Leonard Bernstein. This isn’t about Debussy being the best, but rather, it’s a small tribute to the Frenchman’s unique credentials for testing your hi-fi and, perhaps more importantly, having a lovely time as you do it.

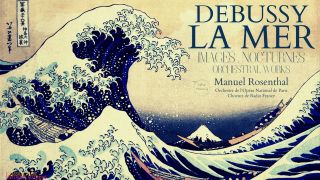

As you probably know, most of Debussy’s music is composed for the piano, and while there are some orchestrated exceptions (see The sea) and a few instances of him straying from the wood and ivory, the vast majority of his works are confined to a single instrument. For purely practical reasons, that makes Debussy’s large catalogue easy to get a handle on – we all know how a piano should sound, and the more of his work you listen to, the more you’ll be accustomed to how the iconic instrument should be reproduced without the distractions of other instruments or flavours obscuring your view. The deceptively simple question we always ask at What Hi-Fi?, in fact, is “Does that piano… sound like a piano?”.

Few composers have ever managed to wring out so much depth and texture from Western music’s most popular instrument. Debussy’s music often sounds simple, but it can be a devil to play thanks to the complexities of the many rather odd chords employed, the rubato (gently quickening and slowing) of its rhythms and the deeply expressive nature of the music as a whole. That last one is the key ingredient, with the best works acting as either mini-stories or as explorations of a given concept, person or emotion: Moonlight (Moonlight), The girl with flaxen hair (The Girl with the Flaxen Hair) or The sea (The Sea), for example.

The more familiar you become with these pieces, the more you will be able to pick out when a system is giving you those feelings and expressing those concepts or whether the music has become rote, soulless and distinctly uninspiring. Debussy paints canvases with his music, but a bad setup will make those beautiful pictures seem like grainy photocopies. The piano itself usually has a very specific timbre, with the music employing frequent use of the sustain pedal and chords replete with plenty of sharps and flats which, in short, gives compositions a glossy, glassy and often ethereal quality.

I’m sure we (or I) have written before that slightly snobbish distinction that listening to music is as much about picking out the spaces in between the notes as it is about listening to the notes themselves, but it really is an apposite aphorism here. Thanks to his frequent pedal use and proclivity for long, lingering keystrokes which are allowed slowly to decay and fall back into silence, Debussy’s work lives or dies on a system that can bring out those patterns of rise and decay with clarity and nuance. As you listen to Saraband or The Girl with the Flaxen Hair, every note should have its own discernible and unique lifespan, arriving with a given volume or tone and then falling away again with just as much character as when it was struck. Great systems will bring out these mini-lifespans, tracking every moment from life to death, while weaker ones will make the experience sound mechanical, flattening the volume of each keystroke and then making each gradual fade-out feel uniform or artificially cut off.

As we always say, it all boils down to a question of emotion, and few composers leaned so heavily into the idea of music as being an emotional experience rather than a technical exercise. Bach remains unrivalled for his technical compositional prowess, but some listeners prefer to pick apart and analyse his, say, use of counterpoint and polyphony rather than sit back and enjoy the music. Debussy’s work is replete with complexity and evidences a deft artistic hand, but his best stuff continually seeks to stir the soul. That makes assessing the merits of a system easy: do these speakers make Saraband sound grave and grand? Do they make Moonlight sound ethereal, almost magical? Do they make Reverie sound like a dream?

Perhaps that’s why we come back to Debussy’s work so often, in that it can be enjoyed and employed on several different levels. You can spend hours assessing whether that minor chord fell away as dramatically on one pair of floorstanders as it did on another, or else muse over the rises and falls of different phrases and patterns like a scholar. Ultimately, though, you can always switch off your brain, sit back and ask yourself that all-important question: “How is this music making me feel?”

MORE:

These are the best classical tracks for testing your system

Enjoy 9 of the best British albums for testing your hi-fi system

Debussy also features on our list of the best piano tracks to test your hi-fi