Paul Knox’s latest book, Lost London: From Crystal Palace to Heston Airport, a History in 25 Missing Buildings, explores lost buildings from the 17th century to the present day, ranging from The Pantheon (now M&S Oxford Street) to the Crystal Palace.

In this abridged extract, the author writes of London’s long lost airport at Heston.

When it first opened, Heston could only cater to private, instructional and club flying, together with a certain amount of charter work; but within a year it had acquired the customs and immigration facilities required by the 1919 International Convention of Aerial Navigation. It was promptly renamed as Heston Airport.

Regular passenger services started in 1933, with Spartan Air Lines’s twice-daily summer service to Cowes on the Isle of Wight the first scheduled service. The flight, by seven-seater Spartan Cruiser aircraft, took 50 minutes, for a cost of 30 shillings return. In 1934, Heston was adopted by Jersey Air Lines with its fleet of de Havilland Express aircraft. Other early routes included Blackpool, the Channel Islands and France.

By 1934, the airport was dealing with nearly 4,000 flights and over 12,000 customs clearances per annum, making the introduction of full air traffic control a necessity. Heston’s passenger traffic continued to double almost annually, and it came a close second to Croydon in the number of flights it handled.

It also became a focus for London’s social elite. Tickets to the annual Garden Party Flying Displays of the Household Brigade Flying Club were reputedly as hard to come by as those for the Royal Enclosure at Ascot. Leading socialites were among the crowds, including HRH the Prince of Wales, who flew to Heston in his own Puss Moth. From the start, Heston had hosted rich private aircraft owners and their friends, who gathered for joyrides, aero racing and aero touring.

In 1930 the London Daily Chronicle carried the news of a group of 20 light aircraft that set off on an 11-day tour of the continent with the likes of ‘Mr Gordon Selfridge; Mr W.D. MacPherson, a rich young sportsman; Mr Chalmers, the racing motorist, and his wife; Mr Jack Shand, a Worcestershire hunting man; Mr Harold Peake, of Bawtry Hall, Yorkshire; Mr John Turner, of the Stock Exchange; and Mr Robert Perkins, engineer. Lady Bailey hopes to join the party, which will contain half a dozen women.’ There was a ‘flying cash box’ containing a large sum of money in six different currencies, to ensure that none of the amateur flyers would be stranded without the means of securing a good dinner. Also reassuring for some Chronicle readers, perhaps, was that: ‘All the tourists are taking evening clothes with them, and reserves of underwear are to be sent by air liner to Prague.’

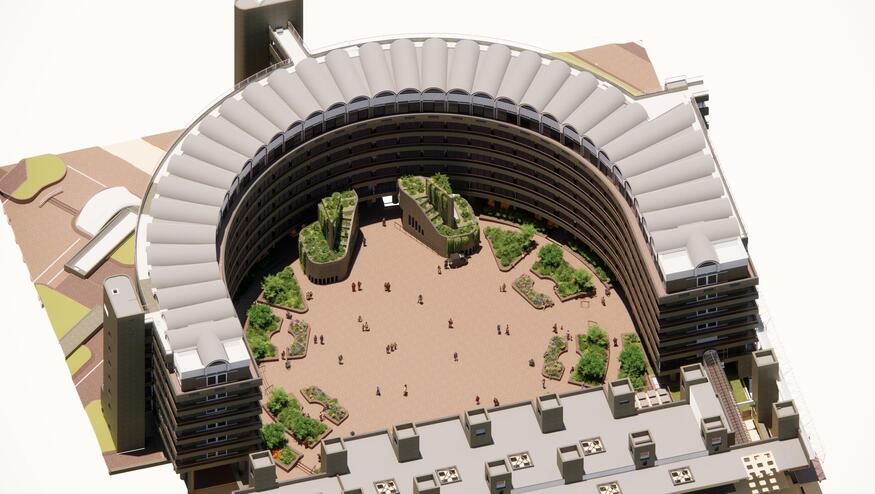

The growth of scheduled passenger services in the mid-1930s gradually overtook private flying from Heston. More importantly, the limitations of the grass fields at both Heston and Croydon were beginning to become apparent: they were simply too small for the take-off and landing of modern monoplanes, such as the DC-3. The Air Ministry was acutely aware of the necessity of addressing the issue before all the available open spaces around London were absorbed by the interwar suburban building boom, and in 1937 it purchased Heston Airport with a view to securing it as part of a prospective London airport strategy. Two government committees were set up to investigate, and dozens of possible sites within Greater London were considered before Heston was earmarked for major expansion as one of four airports to serve London, along with Croydon and new airfields at Fairlop (in Essex) and Lullingstone (in Kent).

Throughout September 1938, Heston featured on newsreels worldwide as the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, flew from Heston to Nazi Germany three times for talks with Adolf Hitler as Germany was threatening to invade Czechoslovakia. After his third trip, Chamberlain returned to Heston brandishing an agreement that seemed to have removed the imminent threat (but only by allowing Hitler to annex parts of Czechoslovakia). Speaking at Downing Street a short while later he famously claimed that it promised ‘Peace for our time’. A year later, with the Second World War under way, he was left with a reputation for appeasement and political naivety. Still, as Michael Law points out, Chamberlain’s arrivals at Heston were ‘greeted by thousands of suburban residents who had found hope that their new houses were no longer under the threat of being destroyed by German bombers’.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, all civil flying was suspended. Heston became the home of wartime photographic reconnaissance and hosted a succession of units, beginning with RAF Spitfires and Hurricanes controlled from Northolt and going on to include a Polish Spitfire squadron, night fighter operations, early radar countermeasures and, later in the war, transient US Army Air Force units that included the USAAF Headquarters Squadron, the 27th Air Transport Group, the 86th Air Transport Squadron, the 325th Ferrying Squadron and the 112th Liaison Squadron. One of the hangars was destroyed by a German parachute mine in 1940, but otherwise Heston was unscathed.

With the war over, the plan for four London airports was scrapped: by now Croydon and Heston were both surrounded by urban development, and incapable of handling the expected increase in civil traffic. Heathrow, with the country’s longest runway (that had been built to accommodate Lancaster bombers during the war), was identified as the nucleus for a postwar civil airport, and in 1946 the newly instituted Ministry of Civil Aviation took over the old RAF aerodrome at Heathrow and renamed it London Airport. Heston was used by 701 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm, until 1947, when it was finally closed because its proximity to Heathrow posed an air safety hazard. The old perimeter track was used for motor racing for a short time, before parts of the field were sold off to Heston and Isleworth local authority for social housing. The rest of the site was still owned by the government, and part of it was used in the mid-1960s for the M4 motorway, including the Heston Services complex.

The only survivor was Austin and Murrell’s concrete hangar, eventually listed, in 2009, as a Grade II building by English Heritage (now Historic England). The hangar is currently part of an industrial park, and is occupied by a cash-and-carry firm.

Lost London: From Crystal Palace to Heston Airport, a History in 25 Missing Buildings, by Paul Knox, published by Yale University Press London. Published 28 April 2026. Available for pre-order now.