Being politically correct is kind of boring,” Paul Schrader tells me. It’s a mantra the director and screenwriter has lived by throughout his nearly 50 years of movie-making – years that have made him cinema’s supreme chronicler of male angst and existential anguish. Troubled men crop up in most of his films: the glossy sex work thriller American Gigolo (1980), the erotic horror Cat People (1982) and the neo-noir Affliction (1997).

When he was 26, he wrote the screenplay for Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) – he’d go on to write or co-write Scorsese films including Raging Bull (1980), The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) and Bringing Out the Dead (1999) – in the process creating the ultimate movie anti-hero, the lone wolf Travis Bickle played in such blistering fashion by Robert De Niro. Fifty years on, Schrader remains as preoccupied as ever with masculinity at its most twisted. In his most recent film, this year’s Master Gardener, the main male character is a horticulturist with a white supremacist past.

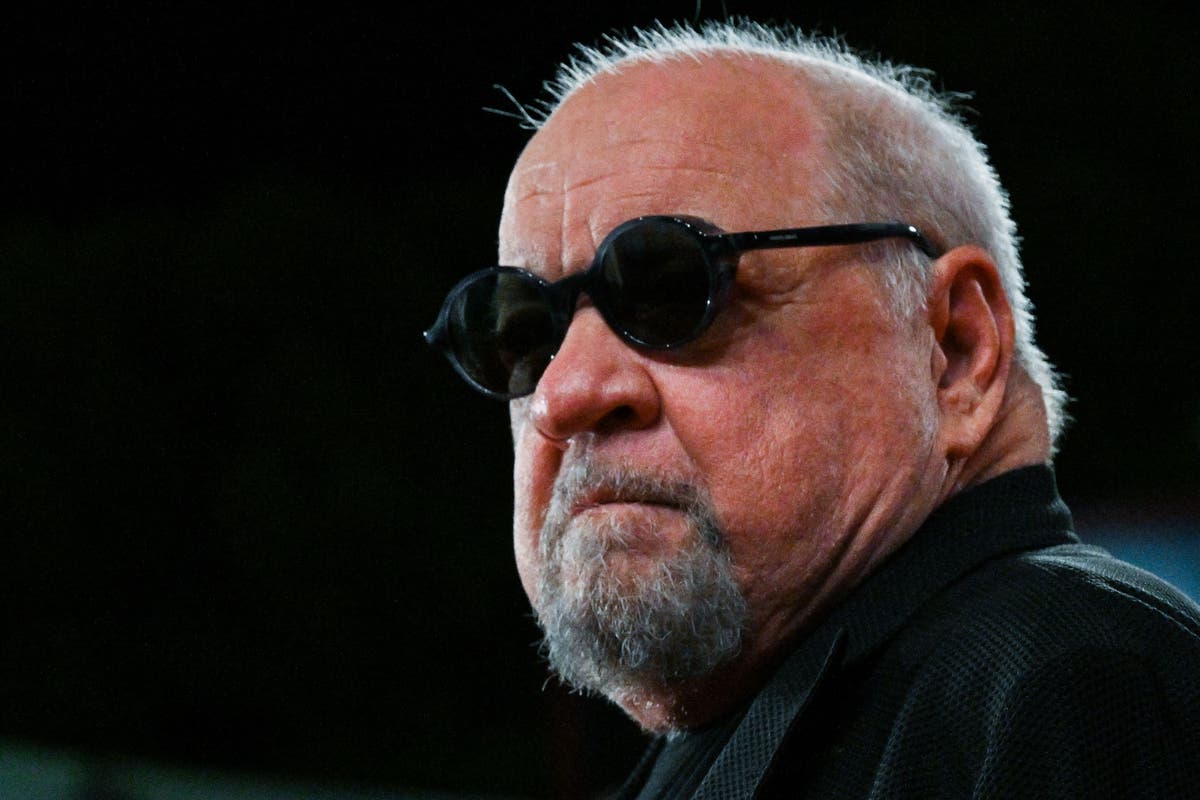

Schrader is now 77, his biggest problem in recent years being his health. He still has long Covid, and has been in the hospital three times in recent months with bronchial pneumonia. “My ability to breathe will never be what it was,” he says. For a while, he was housebound in New York, unsure if he’d work again. Now, though, he’s up for travelling. This week, he is heading to Avellino in Italy to present a masterclass and receive the Laceno d’Oro film festival’s Lifetime Achievement Award. He’s also just finished another film: Oh, Canada, which stars Saltburn’s Jacob Elordi, Uma Thurman and Richard Gere, marking a reunion between the pair more than 40 years after American Gigolo.

Those who remember Gere as the Adonis-like, Armani-clad male escort in that film will be startled to learn that he is wheelchair-bound in Oh, Canada. “He is 74 [but] is really in great shape,” Schrader says. It meant the actor had to be plastered in make-up so he looked suitably sickly. Gere and Elordi play the same character at different points in his life, with Schrader calling the project “a film about dying”. It’s an adaptation of Foregone, a 2021 novel by his late friend Russell Banks, about a radical Sixties documentary filmmaker looking back on his youth while riddled with cancer. (Affliction, for which James Coburn won an Oscar, was also taken from a Banks novel).

The dying process depicted in Foregone, Schrader says, ended up mirroring how Banks would ultimately die from cancer in January 2023, while it was his own health crisis that inspired him to get to work on the film. “[I thought,] if I am going to make a film about dying, I had better make it quick.” During the production of Master Gardener, Schrader had been rushed to the emergency room. He could hardly breathe, let alone stand. He was able to finish the film, but worried in the aftermath that it might have been his last. With Oh, Canada wrapped now, though, he’s unsure what the future holds. “I’ve already made my film about dying, what do I do next?”

Schrader is speaking to me by Zoom from his New York apartment. He cuts a grizzled figure. His voice is husky and he sounds a little breathless. You could almost mistake him for the Walter Huston character, the ornery old gold prospector with the mordant, fatalistic sense of humour, in classic Hollywood movie The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). He’ll answer any question, seeming to prefer the curveballs to the straightforward ones.

Anyone who follows Schrader on social media will be used to his outspokenness. He began his career as a film critic, and uses Facebook primarily as a tool to post insightful and very waspish remarks about new releases. In October, for example, he posted his thoughts on Saltburn, Emerald Fennell’s macabre Brideshead Revisited pastiche, writing that it “flips The Talented Mr Ripley formula in which the lower class arriviste undermines the establishment with his charm and beauty.” He continued: “In Saltburn the lower class boy is plain and the object he pursues is beauty personified. It’s an inversion which should not work. And it doesn’t.” I put it to him today that his take on the film was “slightly withering”. “It is a bad film,” he promptly replies. “Instead of ‘withering’, you could say a slightly accurate review.”

Lindsay Lohan lost the 10 most valuable years of a young actress’s life – she will never get those back

He describes Facebook as a “very efficient” way of scratching a creative itch, though admits to sometimes clamming up when it comes to his opinions on certain films. “I can’t really be a film reviewer because there are things you can say that are detrimental to your career,” he says – he tends to avoid criticising actors, for instance, just in case he’ll try to work with them at a later date. He’ll also never be critical of old colleagues and friends. If, for instance, he had criticisms of Scorsese’s work, he would “tell Marty” directly rather than post about it.

I ask him what he thinks of so-called “cancel culture”. “There was a point in the #MeToo movement when if a woman accused a man of something, it was de facto true,” he says. “That has now swung back. If there is someone accusing [an actor of sexual assault], most women will say, ‘let’s look into this and see what is there’. [The accuser] is not automatically telling the truth.”

Access unlimited streaming of movies and TV shows with Amazon Prime Video

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up

Access unlimited streaming of movies and TV shows with Amazon Prime Video

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up

Has he ever worried about being “cancelled” himself? “You have to worry about it because it can be done on so little evidence,” he claims. “Particularly at the height of the #MeToo movement, all you would need is someone pointing a finger at you and other people would say, ‘Of course he is [guilty].’ Fortunately, I didn’t do anything to merit that and nobody hated me enough to do it.”

Masculinity at its most twisted: Robert De Niro in ‘Taxi Driver’

(Shutterstock)

He is no stranger to being criticised for his opinions, though. For years, Schrader has expressed his eagerness to work with Kevin Spacey, who in July was found not guilty of sexually assaulting four men following a trial in London. The American Beauty star had long denied multiple allegations of sexual misconduct. “People responded as if I had said I would kick a homeless man,” Schrader says. “I mean, Kevin Spacey is a great actor. He won two Oscars. He was found not guilty. Why would I not work with him?”

Schrader’s creative vision often puts him in the crosshairs of producers and financiers, too. His 2003 prequel to The Exorcist, starring Stellan Skarsgård, was deemed not scary enough by its backers, then scrapped and remade by a different director (his film would eventually surface in 2005, under the title Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist).

In 2014, his Nicolas Cage thriller Dying of the Light was taken out of his hands by its producers and recut against his will. Both he and Cage disowned the official cut. “I went back to re-edit a kind of gonzo version of it, which I called Dark,” he remembers. He then put it online via the internet’s leading piracy website. “Once you stick something on the web, it is going to be there more or less forever.” Dark was taken down from some sites, but would immediately pop up elsewhere. It’s a rare example of a filmmaker being fully complicit in the pirating of his own work – and most fans have applauded him for having the gumption to restore his own film to its proper state.

Armani-clad male escort: Richard Gere in ‘American Gigolo’

(Shutterstock)

In recent years, Schrader’s work has drawn repeated raves, most notably his 2017 film First Reformed, an existential thriller starring Ethan Hawke – it earned him a Best Original Screenplay Oscar nomination, his first from the Academy. A few years earlier, though, he was in a creative tailspin and had a gloomy perspective on the future of film. His maligned erotic drama The Canyons (2013) starred Lindsay Lohan and the porn star James Deen, and opened with a grim montage of closed-down cinemas, their facades boarded up, their auditoriums peeling and falling apart. Schrader also gave a series of interviews at the time of the film’s release in which he suggested movies were in their death throes. He hasn’t exactly recanted that stance, but he recently described Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster hit Oppenheimer as “the most important film of this century”. He was a big fan of Barbie, too.

“I am glad the theatre-going experience has not died off to the degree it looked like it would,” he says. “But it is still dying. It will continue to die and become a more and more niche way to see movies.” He predicts a future in which cinema will still exist but, like jazz or classical music, will lose its profile.

He is personally still watching plenty of new films, though, and is quick to share his opinions on them with me. He has mixed views on Baz Luhrmann’s 2022 biopic Elvis, suggesting it was “a little too much checking the boxes”. He also found Sofia Coppola’s new movie Priscilla, about Presley’s wife and starring his Oh, Canada co-lead Jacob Elordi as Elvis, “more interesting” because “it didn’t have the music” and focused on a different aspect of Presley lore.

He thinks Presley himself “p***** away his gift and his ability to reach people”, comparing him unfavourably to the likes of Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen, artists who, he says, “defined a generation and continue to do so not only with their hits but with their ideas”. Naturally, we move on to Lindsay Lohan. She and Schrader had a combative relationship on the set of The Canyons, the actor fresh from a stint in jail and eager to restart her career, and Schrader in need of a hit. It was a recipe for disaster. At one point, as reported in an infamous New York Times article on the film’s production, Schrader took off his clothes and directed Lohan naked in order to make her comfortable before shooting a sex scene.

A chaotic set: Lindsay Lohan in ‘The Canyons’

(Shutterstock)

“Lindsay was more or less at the end of her rope at that time,” Schrader remembers today. “I thought she could pull it together but I was wrong. Now, she has pulled it together but it has taken time. She is a mother and she has now made a Christmas movie. But she lost the 10 most valuable years of a young actress’s life – she will never get those back.”

As for Schrader, it’s arguable – despite his recent health issues – that he’s in his prime. No longer allied with the studios and comfortable working with low budgets, he can retain final cut on his films. A biography about him is in the works, and he’s currently completing post-production on Oh, Canada. He’s also been busy experimenting with artificial intelligence, and specifically the chatbot ChatGPT. He recently asked the AI tool to compose a song for him in the style of Dylan – and it obliged. “AI knows every Bob Dylan song by heart,” he marvels. “There are hundreds and hundreds of them. You can say, ‘Give me a Dylan song from the Eighties, give me a Dylan song from the Nineties…’ and it will write one for you. [What it produced] wasn’t a particularly good song – but Bob wrote a lot of bad songs too!”

Talking up the plusses of AI won’t endear Schrader to detractors of the technology, but by now Schrader is used to maulings. “Film directors are alpha types, whether they are men or women,” he says. “Your instinct is: give me a chair, give me a whip and put me in that room with the lions. I’ll make them sit.”

The Laceno d’Oro International Film Festival runs until Sunday 10 December, with the ceremony for the Lifetime Achievement Award and Schrader’s masterclass taking place on Friday 8 December