An Investigation into the Relationship between Early Exposure and Brand Loyalty

2013

A PSYC3520 Major Project supervised by

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Psychology (BSc Hons)

and in agreement with the University of Leeds’ Declaration of Academic Integrity

| Contents | Page |

|---|---|

| Abstract | 2 |

| Introduction | 3 |

| Brand Loyalty | 3 |

| Early Exposure | 5 |

| Early Exposure and Earliest Memories | 6 |

| Food: Brand Loyalty and Earliest Memories | 8 |

| Aims and Hypotheses | 10 |

| Method | 11 |

| Sample | 11 |

| Materials and Measures | 11 |

| Design and Procedure | 12 |

| Ethics | 13 |

| Analysis | 13 |

| Results | 14 |

| Discussion | 22 |

| Understanding the Relationship Between Early Exposure and Brand Loyalty | 23 |

| Early Brand Exposure: Ethical Considerations | 25 |

| Exploring The Roles of Brand Trust and Brand Affect | 26 |

| Utilizing Childhood Memories to Understand Brand Loyalty | 28 |

| Limitations and Implications for Future Research | 30 |

| Conclusion | 32 |

| References | 33 |

| Appendices | 42 |

Abstract

The importance of understanding the factors that contribute to brand loyalty has risen notably in recent years. This is partly attributed to a marked decrease in brand loyalty observed in Western societies, and therefore consideration of the factors that could improve this reduction is fundamental. Accordingly, the relationship between age of exposure and brand loyalty is explored to investigate if early exposure to brands has an influence over individuals’ current brand loyalties. Assessing if early exposure is a factor that brands should consider when endeavouring to obtain brand loyalty from their consumers. In line with previous research (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001) the relationships between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty are explored. In addition, the age and nature of participants’ earliest autobiographical memories are investigated. The study was conducted through an online questionnaire (n=137) using questions adapted from previous studies (Morrison & Conway, 2010, Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). Results showed a significant negative correlation between age of exposure and brand loyalty for one of the food products. Significant positive relationships were found between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty for all 7 products; brand trust was found to be the strongest predictor of brand loyalty in all cases. Analysis of participants’ earliest food and brand memories indicated earliest memories with food were prior to earliest brand memories. Gender had no significant effect on the age at which participants recalled their earliest memories. In line with previous research (Lupton, 1994), participants’ earliest memories of food tended to be related to familial relationships and environments. Finally, the implications of ensuring brand loyalty through early exposure are considered.

Introduction

Brand Loyalty

Ensuring brand loyalty is a considerable and on-going challenge for multinational companies, as there is no definitive answer or quantifiable procedure as to how to ensure a consumer will remain loyal to a given brand. This pressure is continuously experienced by brand owners and their marketers and encapsulates the wider implications of this study. A brand can be defined as; a distinguishable product, which consumers believe matches their distinctive and required needs; additionally, a brand’s ability to defend itself against competition denotes its success (de Chernatony & McDonald, 1992). Brand loyalty can be defined as; a strong reliable assurance to repurchase a favoured product in the future, thus causing the reoccurrence of same-brand purchase behaviour (Oliver, 1999). In addition to there being no one answer to ensure brand loyalty, it has been recognised maintaining brand loyalty becomes an even greater task in today’s challenging economic environment (Van Steenburg & Spears, 2011), as individuals become more frugal with their disposable expenditure, and seek to purchase cheaper non-branded alternatives (Pepper, Jackson & Uzzell, 2009; Heinz Annual Report, 2012). Consequently, companies, both multinational and smaller sized, are continuously attempting to understand the most effective way to market their brands to ensure existing consumers remain loyal. This is a significant challenge for companies, as it is known effective marketing depends entirely upon the specific target consumer (Kotler, 1972), therefore understanding why a particular demographic remains loyal to a given brand is a complex process.

There is no doubt multinational companies are aware of the power and importance of brand loyalty, in particular they recognise the risk that even their most loyal consumers might explore cheaper alternatives, particularly in the current economic environment. Unilever highlighted in their Annual Report (2012), the role of brand development is central to their business model and forecast growth. Moreover, the report underlined the importance of fostering and building consumer-brand relationships. More recently the Internet has become a tool companies utilise to develop consumer-brand relationships, and maintain consumer loyalty. In particular, the focus has been on ever-growing social media platforms, such as Facebook (www.facebook.com) and Twitter (www.twitter.com). Facebook, created in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg, is now the second most used website in the world, with over a billion users each month, and on average 618 million active daily users, reported in December 2012 (Facebook Newsroom, 2013). Brands benefit from the ability of having direct and immediate contact with consumers, by strengthening pre-existing brand loyalties, and developing new ones (Weintraub, 2012). These platforms have allowed brands to foster deeper relationships with their consumers, building brand trust, and in turn brand loyalty (Laroche, Habibi & Richard, 2013). Importantly, as noted by Unilever in their Annual Report (2012), due to the increasing use of social media platforms, which now allow consumers to easily broadcast their brand preferences and opinions to thousands of individuals, it is fundamental brands form strong positive relationships with their target consumers. Consequently, an understanding of the specific factors contributing to and ensuring brand loyalty is necessary. Although the contributing factors to brand loyalty are frequently explored, as noted by Schmitt (2012), previous research has been largely non-conclusive. Nevertheless, Schmitt emphasises this research should not be disregarded. A few examples from the literature which are thought to aid the facilitation of brand loyalty can be highlighted; emotion based consumer-brand relationships (e.g. Evanschitzky, Iyer, Plassmann, Niessing & Meffert, 2006; Baloglu, 2002), product involvement (e.g. Quester & Lim, 2003), brand ethics (e.g. Singh, Iglesias & Batista-Foguet, 2012), brand trust and brand affect (e.g. Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001), and more recently social media strengthening brand trust (Laroche et al., 2013). However, as highlighted by Schmitt (2012), previous models generally disregard psychology by primarily focusing on an outcome such as brand loyalty, as opposed to exploring the psychological underpinnings causing the outcome. Hence, this is where the current study is introduced, whilst still interested in the outcome of brand loyalty; the main aim of the current study is to identify if early exposure has a role in ensuring brand loyalty. There are many ways in which brand loyalty can be tested, largely depending on the domain in which it is being studied (Schmitt, 2012). Similar to brand trust, brand loyalty is a concept that is of interest to several disciplines, such as psychology and marketing, thereby making it difficult to test using a single measure (Delgado-Ballester, MunueraAleman & Yague-Guillen, 2003). This study will test brand loyalty using a highly cited measure put forward by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001); frequently used as it encompasses both behavioural and attitudinal loyalty, and therefore is regarded as a holistic and robust measure (Sung & Kim, 2010). Schmitt (2012) emphasised the need for future research to further investigate the role of brand affect; one of the core constructs included in his consumer psychology model. Therefore, similar to previous studies (e.g. Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001, 2002; Sung & Kim, 2010), the current study will also measure brand trust and brand affect utilising questions derived from Chaudhuri and Holbrook’s (2001) initial study. In accordance with definitions used by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), brand loyalty will be defined in the current study using the definition previously mentioned (Oliver, 1999). Brand trust will be defined as; a disposition shown by users of a particular brand to believe in its capability to carry out its purpose (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). Moreover, brand affect will be defined as; a brand’s ability to instil a positive emotional reaction in its users, due to its usage (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). In addition, and most importantly, age of exposure will be measured in the current study.

Early Exposure

More closely related to psychological literature it has been proposed that early exposure to brands might be a key factor in establishing and ensuring brand loyalty. Fournier (1998) in a now regarded seminal study highlighted consumer brand relationships made early in life, which are formed by meaningful others, are frequently shown to be extremely strong. More recently, Ji (2002) put forward that the affiliations children develop with brands early in life are more deeply formed than those made later. The emotional significance of early exposure to brands should be recognised, as child-brand relationships form the basis of brand relationships later in life (e.g. Braun, Ellis & Loftus, 2002). Furthermore, Braun-LaTour, LaTour and Zinkhan (2007), stated early exposure to brands provides the basis for poignant attachments. This growing area of consumer psychology has prompted the current study, as it has been noted the concept of early exposure has received less attention in marketing literature than others previously mentioned, for example brand trust (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001). As recognised by Richard Garfein in an article for the American Psychological Association (1997), research conducted concerning business development within a company is infrequently published, or made available universally. It should therefore be underlined that research of this nature has quite possibly been carried out prior to this study by multinational companies, which are solely interested in growing brand loyalty for their own brands against their competitors. This highlights the need for an objective, systematic and unbiased study, where results are non-brand specific, and can be utilised by a range of brands and product categories. Unlike the majority of previous studies of this nature conducted in the United States (e.g. LaTour, LaTour & Zinkhan, 2010), the current study will be conducted in the United Kingdom. Moreover, it will not test individuals with specific knowledge in the area; as observed in Chaudhuri and Holbrook’s study (2001), which tested senior-level market research students.

Early Exposure and Earliest Memories

It is recognised that as the current study aims to explore age of exposure to brands, in an attempt to understand its relationship with brand loyalty, participants will be required to recall when they were first exposed to a brand. Consequently, it is predicted participants will predominately be recalling autobiographical memories from their childhood. Autobiographical memory is a form of episodic memory related to the self, and helps individuals shape and define themselves (Conway & Rubin, 1993). Moreover, as participants will be specifically asked for their earliest memories, it is important to outline the existence of childhood amnesia. Childhood amnesia was first introduced by Miles in 1893, and later termed infantile amnesia by Freud in 1899. Childhood or infantile amnesia refers to an observed significant reduction in the number of autobiographical memories recalled by individuals, typically before age seven, and in particular before four years old (Peterson, Grant & Boland, 2005). On average adults’ first memories are between the ages of three and four years old (Jack & Hayne, 2010). Nevertheless, there is no doubt age differences exist across individuals (Jack & Hayne, 2007). However, this is not representative of an individual’s current age, as previous research exploring infantile amnesia has shown no significant difference between the ability of older adults and adolescence to recall memories from their childhood (e.g. Peterson, et al., 2005; Kingo, Bernsten & Krøjgaard, 2013). Thereby, providing justification for the current study to focus on a broad age range of participants. In addition, gender differences have been highlighted; suggesting females are able to recall earlier autobiographical memories than males, however inconsistencies in the literature can be observed (e.g. Mullen, 1994; Rubin, Schulkind & Rahhal, 1999).

It has also been recognised there is an even greater reduction in adults’ abilities to recall memories under two years old, where the majority of individuals are unable to recall any (Josselyn & Frankland, 2012). This parallels the pre-verbal period when individuals are unable to communicate through language (Morrison & Conway, 2010). In Morrison and Conway’s (2010) study, participants’ earliest childhood memories were explored in response to fifty cue words. Participants were also required to provide the age of when they had each memory on a seven point Likert scale. Morrison and Conway found participants’ earliest memories for each of the cue words was consistently later than the age at which they first acquired the word; this was reliably found across the age range of participants. It was noted participants’ age of acquisition for more abstract words such as ‘vase’, was older than that for more commonly used words in childhood such as ‘jelly’. Consequently, Morrison and Conway postulated that without the formation of conceptual information relating to a specific word, individuals are unable to access episodic memories relating to that word; underlining one of the causes of infantile amnesia. Using a similar method to Morrison and Conway (2010), participants in the current study will be required to recall their earliest memories in response to product cue words, stating the age of when they had each memory. It is postulated that by allowing participants to recollect their earliest autobiographical memory of each product, recall of when they were first exposed to their preferred brand of each product will be more easily facilitated, as it has been suggested that during the process of autobiographical recall, individuals can feel as though they are re-experiencing events (Schacter, 1996).

There is evidence to support the projective method used in the current study; Josselson (2000), highlighted it has long been known that individuals’ earliest childhood memories have the ability to signify their current internal opinions, providing a useful insight for researchers (Adler, 1937). It has also been recognised events that take place early in individuals’ lives have more powerful effects than if they were experienced later (Hayne, 2004). Most notably, with regards to this study, previous research has found exploring individuals’ earliest memories from childhood is a useful tool to understand present brand affiliations; it allows for an understanding of how brand relationships were first developed (Braun-LaTour & LaTour, 2007). Exploring childhood memories of brands There is evidence to support the projective method used in the current study; Josselson (2000), highlighted it has long been known that individuals’ earliest childhood memories have the ability to signify their current internal opinions, providing a useful insight for researchers (Adler, 1937). It has also been recognised events that take place early in individuals’ lives have more powerful effects than if they were experienced later (Hayne, 2004). Most notably, with regards to this study, previous research has found exploring individuals’ earliest memories from childhood is a useful tool to understand present brand affiliations; it allows for an understanding of how brand relationships were first developed (Braun-LaTour & LaTour, 2007). Exploring childhood memories of brands also helps to understand affective attachments and reasons for current brand choices (Braun et al., 2002). Braun-LaTour et al., (2007) in an attempt to understand brand meaning, proposed that individuals’ earliest product memories could be utilised as a means of understanding their current product relationships. They recognised individuals’ earliest memories were able to account for later brand preferences; interestingly it has been proposed earliest childhood memories are in fact more beneficial to study than memories from adolescence, when attempting to understand current brand loyalties (LaTour et al., 2010).

In view of previous research highlighted (Hayne, 2004; Braun et al., 2002; Braun-LaTour et al., 2007; LaTour et al., 2010), this study aims to explore early exposure to brands, by utilising participants’ earliest autobiographical memories for various products, with a central aim to understand if there is a relationship between early brand exposure and the strength of current brand loyalties. To the best of our knowledge, this projective technique has not been previously used to understand factors contributing to individuals’ current brand loyalties. In addition, the data collected from participants’ earliest autobiographical memories, will aim to underline the importance of investigating childhood memories (Hayne, 2004).

Food: Brand Loyalty and Earliest Memories

From evaluation of previously published research, it became apparent that food is a central part of children’s upbringing in Western society (LaTour et al., 2010); children are exposed to food products on a daily basis (Ji, 2002). With this in mind, it would appear likely that memories of food products will be salient in individuals’ recollections of childhood. In 1994, Lupton investigated the themes and significance of early everyday food memories in a population of Australian students. Lupton found several participants’ recollected food memories were strongly related to family relationships and mealtime interactions. Since Lupton found childhood memories of food tended to include reference to influential others, a parent for example, it is expected that food memories will be prominent in participants’ recollections of childhood. As these memories are likely to involve salient emotions, places and prominent people (Lupton, 1994), there is strong suggestion that early exposure might aid as a powerful tool for food brands. In addition, it has been suggested attachments and loyalties made towards food products may differ to those formed to other products (e.g. LaTour et al., 2010). From review of previous research it is apparent the product category that has been of key focus when examining factors contributing to brand loyalty is automobiles (e.g. Braun-LaTour, et al., 2007; Zehir, Şahin, Kitapçı, & Özşahin, 2011). To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has investigated the relationship between early exposure and brand loyalty on a range of food products in the United Kingdom. Consequently, this study aims to explore the relationship between age of exposure and subsequent brand loyalty to food brands, through utilising individuals’ earliest childhood memories of food and branded products.

Aims and Hypotheses

Taking into consideration research previously highlighted, the current study aims to investigate if early exposure has a role in ensuring brand loyalty. As the primary research question remains exploratory, no formal hypothesis can be made. However, the exploratory hypothesis states there will be a relationship between age of exposure and brand loyalty. Furthermore, as previously tested by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), the relationships between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty will be investigated. This study aims to replicate the findings of Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001). Therefore, it is hypothesised there will be a significant positive correlation between brand trust and brand loyalty; as brand trust increases, brand loyalty will increase. Likewise, it is hypothesised there will be a significant positive correlation between brand affect and brand loyalty; as brand affect increases, brand loyalty will increase. In addition, as the current study will utilise individuals’ earliest childhood memories as a means of exploring the role of early exposure, the age and nature of participants’ earliest food and brand memories will be investigated.

Method

Sample

203 participants were recruited via an opportunistic sampling method to an online questionnaire; links to the questionnaire were emailed to friends and family, posted on Facebook (www.facebook.com) and Twitter (www.twitter.com) websites, and University of Leeds psychology students were able to complete the questionnaire via Leeds Participant Pool Scheme (http://leeds.sona-systems.com). The age range of respondents was from 16-64 years, with a mean of 23 years old; 169 females and 34 males completed the questionnaire. Participants were required to be English speaking, over 16 and under 70 years old. Participants who had not answered all questions were removed from the data set; it was important the questionnaire was only answered by consumers of all 6 food products. For this reason, analysis was only conducted on 137 participants (24 male, 113 female). The mean age of this sample was 23 years, with an age range of 16-64 years old.

Materials and Measures

Food products were chosen after researching several food supermarket websites; Asda (www.asda.com), Tesco (www.tesco.com), Morrisons (www.morrisons.co.uk), Ocado (www.ocado.com) and Waitrose (www.waitrose.com). A pilot study was conducted to test the reliability of the questionnaire and identify questions that may be misinterpreted. 13 participants completed the 39 item pilot study (4 male, 9 female) with a mean age of 22 years. The following food products were included in the pilot study: tea, coffee, tomato ketchup, butter, bread, fruit juice, soup, yoghurt, mints and chewing gum. Following the pilot study, certain food products were removed, such as; yoghurt, coffee, mints and chewing gum. These products did not demonstrate easily distinguishable brand choice due to the dominance of particular brands, such as Wrigley, in the mints and chewing gum category. Additionally, questions were modified, for example; participants were asked to provide as much detail as possible when recalling their earliest food memories.

The 71 item online questionnaire used questions adapted from both Morrison and Conway’s (2010) and Chaudhuri and Holbrook’s (2001) studies. Measures of brand trust, 12 brand affect and brand loyalty were constructed using questions from Chaudhuri and Holbrook’s (2001) study. Brand loyalty was measured using 4 statements based on purchase and attitudinal characteristics of brand commitment put forward by Jacoby and Chestnut (1978), as tested by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001). Both statements ‘I will buy this brand next time I buy [product]’, and ‘I intend to keep purchasing this brand’ measured purchase loyalty, with a coefficient alpha of .90; meeting the required .70 (Nunnally, 1978). Whereas the statements ‘I am committed to this brand’, and ‘I would be willing to pay a higher price for this brand over other brands’ measured attitudinal loyalty, with a coefficient alpha of .83. Brand trust was measured using the following 4 statements; ‘I trust this brand’, ‘I rely on this brand’, ‘This is an honest brand’, and ‘This brand is safe’, with a coefficient alpha of .81. Brand affect was measured using 3 statements; ‘I feel good when I use this brand’, ‘This brand gives me pleasure’, and ‘This brand makes me happy’ with a coefficient alpha of .96.

Questions asking participants for their earliest food or brand memories were adapted from Morrison and Conway (2010), ‘Please recall and write down your first memory you had with [product], (provide as much information as possible).’ It was noted from Morrison and Conway’s study that emphasis should be made for participants to provide as much information as possible. When asked to indicate the age when they had each memory, the most frequently used 7-point Likert scale testing age of acquisition was utilised; 0-2, 3-4, 5-6, 7-8, 9-10, 11-12 or 13+ years old.

The online questionnaire was constructed on Bristol Online Surveys (BOS) (http://www.survey.bris.ac.uk), and launched on 20th November 2012. BOS allowed for data collection and storage of participants responses, which were then exported when the questionnaire closed on 4th February 2013. To complete the questionnaire participants required a computer, keyboard, mouse and Internet connection.

Design and Procedure

A correlational research design was adopted. The predictor variables were age of exposure, brand trust and brand affect; the outcome variable was brand loyalty. Upon opening the link (www.survey.leeds.ac.uk/brandpreference/) participants were directed to the questionnaire on the BOS website, where they were presented with an information 13 sheet to which they gave their full consent by clicking ‘continue’. Participants were required to complete the questionnaire in their own time, answering 71 questions. Firstly they had to state their gender and date of birth. They were then required to provide their first memory with food and indicate the age when they had this memory on a 7-point Likert scale previously mentioned. Next they had to state their first memory with a branded product, and indicate the age when they had this memory on a 7-point Likert scale. They were then asked ‘Is there a single brand you feel most loyal towards’, and the age when first exposed to this brand. Measures of brand trust, brand affect and brand loyalty were then taken on a 7-point Likert scale, participants had to indicate their level of agreement from 1= very strongly disagree to 7= very strongly agree, to statements previously mentioned. Following this, they provided their first memory of tea, and the age when they had this memory. From a list of brands participants were then required to select the brand of tea they were most likely to purchase. Relating to that brand of tea they were then asked questions relating to brand trust, brand affect and brand loyalty. Finally, participants were required to provide their age when they were first exposed to that brand of tea. This procedure was then repeated for; fruit juice, tomato ketchup, butter, bread and soup.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted from the Leeds University Ethics Committee before research was undertaken (REF: 12-0209, Appendix 3). Participants were presented with an informed consent form prior to completing any questions, informing that their anonymity would be maintained and that they were free to withdraw at any point without providing reason. At the end of the questionnaire participants were provided Dr Catriona Morrison’s email address for any further information.

Analysis

Statistical software IBM SPSS 20 will be used to analyse the data collected. A correlational analysis will be conducted, followed by a regression analysis. If the data is not normally distributed, logarithm transformations will be used to normalise the data so external validity of the study is maintained.

Results

The aim of this study was primarily to establish if early exposure has a role in ensuring brand loyalty. The exploratory hypothesis stated there would be a relationship between age of exposure and brand loyalty. Additionally, the study aimed to replicate Chaudhuri and Holbrook’s (2001) findings. It was hypothesised there would be a positive correlation between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty.

The normality of the data was examined; logarithm transformations were used to normalise the age of exposure variables for each of the 7 products. Histogram and Normal Q-Q plots confirmed the normality of the data, and on inspection of box plots outliers were removed.

Brand Loyalty

Participants’ (n=137) brand loyalty scores were calculated by averaging their scores (1-7) in response to each of the 4 statements measuring brand loyalty. Table 1 highlights the mean loyalty scores for the brand in which participants felt most loyal to, and the 6 specified food products.

Table 1: Summary of means and standard deviations of brand loyalty scores

| Brand | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Brand most loyal | 5.5 | 0.8 |

| Tea | 4.6 | 0.9 |

| Fruit juice | 4.5 | 0.9 |

| Tomato Ketchup | 5.2 | 1.0 |

| Butter | 4.5 | 0.9 |

| Bread | 4.5 | 0.8 |

| Soup | 4.7 | 0.9 |

The results from Table 1 show the highest mean brand loyalty score (5.5) for the brand to which participants felt most loyal. It is important to note there were no restrictions on product category when participants were asked to state this brand. Consequently, the brand selected could have been non-food related; the most commonly mentioned brands from this question are depicted in Fig 1 below. In Table 1 tomato ketchup can be seen to have the second highest mean brand loyalty score (5.2), exceeding mean brand loyalty values for the other food products, by 0.5. However, the highest variability of brand loyalty scores can be observed for tomato ketchup (SD= 1.0).

Apple Blackberry Cadbury Coca-Cola Colgate Converse Galaxy Green GiantHeinz Kellogg’s Lurpack Mac Marks & Spencer Marmite Tetley Topshop Walkers

Fig 1: Word cloud summarising the most commonly mentioned brands in which participants felt most loyal towards

As stated, Fig 1 condenses the brands most commonly mentioned when participants were asked for the brand to which they feel most loyal. From the sample of 137 participants, 28% stated the brand they felt most loyal to was Heinz, 9% Cadbury, 7% Apple, 5% Coca-Cola, and finally 4% Marmite. The remaining 47% of participants either stated they felt most loyal towards a brand not mentioned by more than two other participants, or they did not have a brand to which they felt most loyal.

For product specific brand preferences (tea, fruit juice, tomato ketchup, butter, bread and soup), Heinz significantly led for both tomato ketchup and soup products; 95% of participants selected Heinz as the brand of tomato ketchup they would most likely purchase, and 59% of participants selected Heinz as the brand of soup they would most likely purchase.

Age of Exposure

From analysis of participants’ age of exposure scores it was found the data was marginally positively skewed. Therefore, common logarithm (log base 10) transformations were used to normalise the data for statistical analysis.

| Product brands | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Brand most loyal | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| Tea | 2.7 | 1.3 |

| Fruit juice | 2.5 | 1.4 |

| Tomato ketchup | 1.7 | 0.7 |

| Butter | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| Bread | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| Soup | 2.3 | 1.3 |

Table 2 highlights the means and standard deviations of the age of exposure scores for any unspecified brand to which participants felt most loyal, and brands associated with the 6 specified food products. It is important to note that the mean age of exposure in Table 2 is not specified in years, but on a scale from 1-9. Tomato ketchup brands show the youngest mean age of exposure; between 4-5 years old (1.7), whereas tea brands highlight the oldest mean age of exposure, between 9-10 years old (2.7). On average the oldest age participants stated they were first exposed to brands from the 6 specified food products, and the unspecified brands they selected they currently felt most loyal brand towards, was 10 years old.

Early Exposure and Brand Loyalty: correlational analysis

Following descriptive analysis of participants’ brand loyalty and age of exposure scores, a bivariate correlation analysis was undertaken to investigate if a relationship existed between the two variables. Analysis conducted on each of the 7 products showed only one significant correlation between age of exposure and brand loyalty. Age of exposure had a significant relationship to brand loyalty for the tomato ketchup product, r = -.18, p < .05. This highlights age of exposure is negatively correlated with brand loyalty; as brand loyalty decreases, age of exposure increases, and vice versa. It was noted that r= – .18 is a small effect size.

Upon finding a significant negative correlation between brand loyalty and age of exposure for the tomato ketchup product, a linear regression analysis was conducted to identify if age of exposure could significantly predict brand loyalty towards tomato ketchup. It was found that age of exposure significantly predicted brand loyalty scores, B = -1.11, t(135) = -2.22, p < .05. Age of exposure explained only 4% of the variance in brand loyalty (R2 =.04, F(1,135)=4.93, p < .05). Therefore, although age of exposure significantly predicted brand loyalty, 96% of the variance in brand loyalty towards tomato ketchup cannot be explained by age of exposure.

Brand Trust and Brand Affect: Tomato Ketchup

In response to finding that age of exposure was unable to account for a significant proportion of the variation explaining brand loyalty for the tomato ketchup product (4%), further analysis was conducted to investigate the contributing role of brand trust and brand affect.

Firstly, correlational analysis was conducted. In line with hypotheses, significant positive correlations were found between brand trust and brand loyalty; r = .71, p < .001, and brand affect and brand loyalty; r = .60, p < .001. Additionally, brand trust and brand affect were correlated; r = .76, p < .001; all correlations demonstrated a large effect size. Upon finding significant correlations, multiple regression analysis was conducted to investigate if brand trust and brand affect were able to explain the unexplained variance in brand loyalty for the tomato ketchup product. A stepwise method was used to identify which variable best predicted brand loyalty; the results from this analysis are highlighted in Table 3.

| Model | Constant | Brand Trust | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.61 | 0.87 | 0.07 | .71*** |

| Model 2 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.07 | .70*** |

R2 = .51 for model 1 (p < .001), ∆R2 = .02 for model 2 (p < .05). * p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

As shown in Table 3 it can be observed that brand affect was removed from the analysis. In Model 1 brand trust alone accounted for 51% of the variance in brand loyalty. Model 2 demonstrates that brand trust and age of exposure in combination accounted for 52% of the variance in brand loyalty (R2 =.52, F(1,134)=5.15, p < .05). Although brand trust significantly increased the amount of variance explained in brand loyalty, 48% of the variance in brand loyalty remains unexplained by this model.

Brand Trust and Brand Affect

Next the relationships between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty were investigated for the remaining 6 products. In line with hypotheses, analysis showed significant positive correlations (p < .001) between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty for the remaining 6 products; all representing a medium to large effect size (r = .41 – r = .69). It was noted that brand trust correlated more strongly with brand loyalty across all product categories. Following this, linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate if brand trust and brand affect could significantly predict brand loyalty. Results showed brand trust and brand affect independently significantly predicted brand loyalty for each of the six products (p < .001). Brand trust accounted for the largest amount of variance (48%) in brand loyalty for tea (R2 =.48, F(1, 135)=122.94, p < .001), and the smallest amount (30%) for fruit juice (R2 =.30, F(1, 135)=56.47, p < .001). Brand affect accounted for the largest amount of variance (43%) in brand loyalty for tea (R2 =.43, F(1, 135)=101.80, p <.001), and the smallest amount (17%) for the brand in which participants stated they were most loyal towards (R2 =.17, F(1, 135) = 26.64, p <.001). Further stepwise multiple regression analysis confirmed that for all 6 products, brand trust was a better predictor of brand loyalty than brand affect and age of exposure.

Earliest Memories

As the current study utilised individuals’ earliest autobiographical memories as a means of exploring early exposure, a further aim was to investigate the age of participants’ earliest food and brand memories.

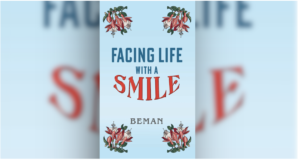

Analysis comparing the age of participants’ earliest memory of food against the age of their earliest memory with a branded product is shown in Fig 2.

As shown in Fig 2 participants’ earliest memory of food tended to be before their earliest memory with a branded product, demonstrated in 91% of the sample. The mean age of participants’ earliest memories of food was 3.5 years old, with a standard deviation of .78, whereas, the mean age of participant’s earliest memories with a branded product was 5 years old, with a standard deviation of .87. When comparing the mean age of these two.

memories against the mean age of participants’ earliest memories of the 6 food products, it was found that on average earliest memories of fruit juice, tomato ketchup, butter and bread were at 5 years old. The average age of participants’ earliest memory for soup was at 5.5 years, and 7 years old for tea. The mean age of females’ and males’ earliest memories were compared for each of the 8 memories asked from participants. A series of independent t-tests showed that there was no significant effect of gender on the age of participants’ earliest memories (p >.05).

Nature of Earliest Memories

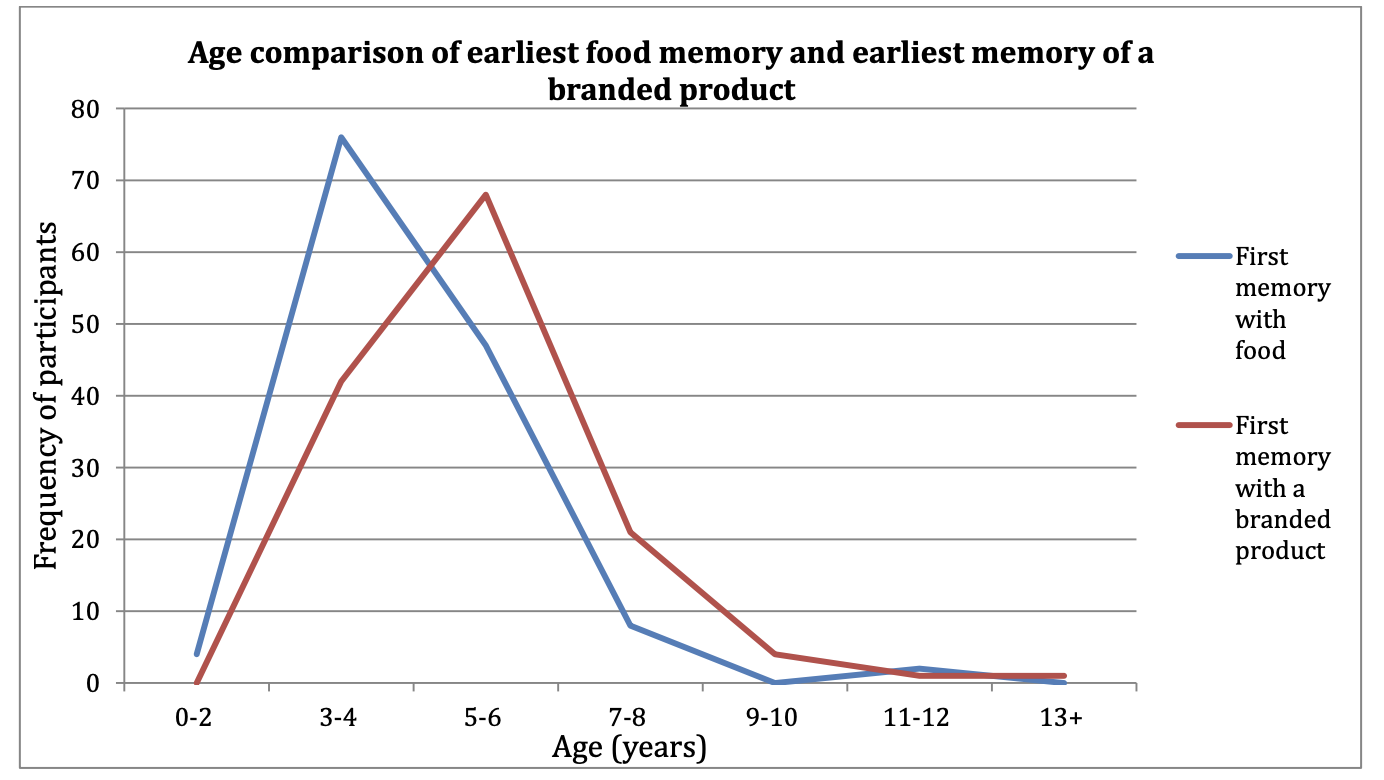

The final stage of analysis involved exploring the content of participants’ earliest food memories. From across the 8 earliest memories asked from participants the most commonly mentioned words are shown in Fig 3.

Word frequencies were calculated on the data represented in Fig 3. It was found that ‘remember’ was the most commonly mentioned word, recalled 352 times. Since this word relates more generally to the task, more importance should be placed on the following non-task related word frequencies. The word ‘Mum’ was the most frequently recalled non-task related word; mentioned 225 times followed by ‘school’ 210, ‘House’ 123, ‘home’ 109, ‘Dad’ 75, ‘birthday’ 60, ‘family’ 62, ‘friends’ 54, ‘parents’ 54, and ‘holiday’ 47 times. ‘Heinz’, although arguably task related was mentioned 87 times; the only brand mentioned at such high frequency.

Lastly, the question asking participants for their earliest memory of food was analysed to identify if any brand names were recalled, this question was prior to any mention of branding, and on average represented participants’ memories of food at the age of 3 ½ years old. The following brands were recalled; Walkers, Heinz, Marmite, Nutella, Dairylea, Lucozade, McDonalds and Walls. Examples of these memories include:

“Walls Ice Cream promotional Freezer in local Grocers shop. I remember what I know now to be an Arctic Roll being advertised on the side and it looked like the pinnacle in the world of Ice Cream.”

“My first memory was having a bottle of Lucozade when I was unwell, my Mother always used to buy me a bottle, just one, to have in small sips to ‘make me feel’ better.”

“Literally not 100% sure if this is my first memory but I do remember sitting in my kitchen at home eating Heinz baked beans with sausages because I remember I was young enough to not know how to pronounce sausages correctly!”

Discussion

This study aimed to explore if there is a role for early exposure in ensuring brand loyalty, by investigating the relationship between age of exposure and brand loyalty. Moreover, in line with previous research (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001) it was predicted there would be positive relationships between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty. In addition, this study aimed to investigate the age at which participants had their earliest food and brand memories, and explore the nature of participants’ memories.

In summary, results from the exploratory study indicate early exposure does not have the strength in ensuring brand loyalty, equal with that observed by brand trust and brand affect. Only one statistically significant negative relationship was found between age of exposure and brand loyalty, for the tomato ketchup product. Albeit, this negative relationship was in line with predictions made, based upon evaluation of previous research (Fournier, 1998; Ji, 2002; Braun et al., 2002; Braun-LaTour et al., 2007); the earlier an individual is exposed to brand, the more brand loyal they are towards that brand in the future. In confirmation with the hypotheses stated, strong positive correlations were found between brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty; brand trust and brand loyalty highlighted the strongest relationship. Both brand trust and brand affect significantly predicted brand loyalty for each of the seven products; as seen in previous studies (e.g. Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Gecti & Zengin, 2013), brand trust was shown to be the strongest predictor in all cases. In addition, participants’ earliest autobiographical memories were explored, it was found participants’ earliest memories of food were before their earliest memories of a branded product; only 9% of participants suggested the contrary. Furthermore, no significant gender differences were found between the ages of participants’ earliest memories, a contentious topic in childhood memory literature (e.g. MacDonald, Uesiliana, & Hayne, 2000; Kingo et al., 2013). Finally, the nature of participants’ earliest food memories were explored; non-task related words used of the highest frequency, were mostly linked to close familial relationships and environments; ‘Mum’, ‘house’, ‘home’, ‘Dad’, ‘family’, ‘friends’ and ‘parents’. Additionally, the only brand mentioned at high frequency in participants’ earliest memories of food was Heinz. The significance of this finding should be noted, as when participants were asked for their earliest memories of food, it was not expected, or 23 requested to state the brand of the product. This was only expected when asked for their earliest memory of a branded product. However, Heinz was voluntarily mentioned 59 times in participants’ earliest memories.

Understanding the Relationship Between Early Exposure and Brand Loyalty

The consumer psychology field is continuously attempting to understand how consumers form relationships with the brands they purchase. Consequently, it is fundamental to establish whether or not early exposure should be a core factor considered when brands endeavour to develop consumer loyalty. Although the role of early exposure in ensuring brand loyalty appears to be questionable from the findings of this study, since to the best of our knowledge this was the first correlational study exploring the relationship between age of exposure and brand loyalty, it is important to evaluate the findings in the wider context of the developing field.

Whilst the study did not find more than one statistically significant negative correlation between the age of exposure and brand loyalty, it is essential to highlight on average the oldest age at which participants stated they were first exposed to the brands in which they currently are ‘most likely to purchase’, was ten years old. Suggesting that the brands which individuals were exposed to at a young age match their current brand purchases, and should not be ignored simply because participants tended not to score highly on the brand loyalty scale. The distribution of participants’ loyalty scores may be due to a variety of factors, for example; Ernst and Young (2012) outlined a study they conducted in 2009 involving approximately 25,000 individuals, from 34 countries. They found that while brand loyalty has increased in Middle Eastern and Northern African regions, it has decreased in Western societies; where only 29% of consumers state brands impact their purchases. Interestingly, it was found that consumers from Middle Eastern and Northern African regions displayed most brand loyalty towards products in the food and beverage category. In all other regions consumers were most brand loyal to telephone contracts. From these findings Olenski (2012) emphasised brands must focus on ways in which they can ensure resilient consumer-brand relationships, particularly in Westernised countries. Similarly, Van Steenburg, and Spears (2011) in an exploratory study, found the current economic climate is a factor that consumers take into account when choosing between, and purchasing branded products. It could be concluded from these findings that 24 participants in the current study may have been reluctant to state they would continue to buy a brand even if they had to pay a higher price for it over other brands. Subsequently, these participants would not have scored very highly on the brand loyalty scale. In addition to the potential global economic strains felt by participants, it is necessary to underline the majority of participants were students and, consequently, may have been reluctant to state they would commit to a brand even if it were the most expensive option. Although at first instance it may appear the relationship between early exposure and subsequent brand loyalty is weak, as with any exploratory study it is important to consider the factors affecting the results based upon the sample investigated.

Unlike previous studies that have investigated the relationship between early brand preference and current brand preference; for example, Guest (1964) concluded from the findings of a longitudinal study brand preferences displayed between early childhood and late adolescence correlated with brands used twenty years later. The current study was only interested in establishing if early exposure to a brand, regardless of its favourability or preference at a young age, had a relationship with current brand loyalties. Accordingly, in contrast to previous studies that have tended to be longitudinal or interview based (e.g. Fournier, 1998; Ji, 2002; LaTour et al., 2010), this study intentionally took no measure of participants’ brand preferences as children. Therefore, it cannot be assumed exposure to a brand at a young age, meant it was an individual’s preferred brand at that time. For example, a participant might have selected Heinz as the brand of tomato ketchup they are most likely to currently purchase, their brand loyalty score towards Heinz could have been high, and they might have selected they were first exposed to Heinz before the age of ten years old. However, it cannot be inferred that when first exposed to Heinz before ten years old, Heinz was the participant’s most favourable brand. Therefore, the inferences made from this study are novel; a correlation between early exposure and brand loyalty places importance on the mere exposure to a brand, as opposed to an explicit brand preference at a young age.

Mere exposure hypothesis was first introduced by Zajonc (1968) and explains an individual’s increased preference for an object or item to which they have been frequently exposed. Zajonc (1968) found individuals’ preferences for Chinese characters increased relative to exposure. Subsequently, the phenomenon has been widely recognised cross culturally and applied to a variety of stimuli (Zajonc, 2001). Janiszewski (1993) found 25 mere exposure to a branded product increased consumers’ preference towards that brand. What is important to highlight is Janiszewski found this increased preference occurred even when an individual was unable to recall the first time they were exposed to the brand, equally when the brand was not purposefully encoded. Emphasising that although participants in the current study may have not consciously recalled or ruminated about the exact age at which they were first exposed to a brand, their initial exposure may have an important role working at an implicit familiarity based level (Yonelinas & Jacoby, 2012; Janiszewski, 1993). Implicit brand memory has recently been considered within consumer psychology (e.g. Plassmann, Ramsøy & Milosavljevic, 2012); receiving attention, as it is recognised utilising individuals’ explicit brand memories heavily relies on subjective brand experiences and preferences. Whilst a more objective measure of brand loyalty could be obtained if individuals utilised implicit memory processes (Nevid, 2010).

It has not always been found that brand exposure increases brand preference. Toomey and Francis (2013) in line with previous research (e.g. Auty & Lewis, 2004) investigated a sample of children to establish whether exposure to branded products actually caused an increased brand preference. Their findings indicated exposure to branded products did not affect children’s attitudes or behaviours towards those specific brands. However, it should be highlighted the effects of exposure were measured immediately, and two weeks after experimentation; their measure did not take into account the effect of exposure over a long time period. Since the current study found on average 10 years old was the latest age of exposure, and the youngest participant was 16 years old, it can be approximated that this study considered the impact of exposure over a minimum period of 6 years; much greater than that used by Toomey and Francis (2013).

Early Brand Exposure: Ethical Considerations

While the current study did not focus on the direct effects of advertising exposure, a relationship found between early exposure and brand loyalty is arguably partly due to effective advertising to which individuals have been exposed. Consequently, it is important to outline the potential ethical issues associated with advertising to children. It is strongly argued that brands should not be permitted to target young children who are unaware of the potential influences of advertising. This is a view held by some members 26 of the American Psychological Association (2000). They argue psychologists should not be working alongside marketers to increase child-brand relationships; instead they should be supporting them to reduce the damaging effects of advertising to children (Kunkel et al., 2004). It has been noted across Europe, children in the United Kingdom watch more television and therefore are exposed to more advertising compared to other European countries (Pine & Nash, 2003). Pine and Nash found the majority of children preferred brands they had previously seen advertised, compared to non-branded alternatives. Bakir and Vitell (2010) emphasised food is central to advertising aimed at children. They highlighted findings by Goldberg, Gorn and Gibson (1978), who found that children exposed to advertisements promoting sugary breakfast foods subsequently displayed preferences towards those products. It could therefore be argued that it is unethical for food brands to aim advertisements at children. However, despite findings indicating young children are unaware of advertisements intentions (John, 1999), it has been shown younger children’s brand preferences are no further influenced by advertisements than older children’s (Chernin, 2008). This finding will both please and displease marketers, as they believe brands should be permitted to advertise to children in an ethical way, but nevertheless would certainly endeavour to increase advertisement to younger children if they knew this would impact their future brand loyalties.

Exploring The Roles of Brand Trust and Brand Affect

It is fundamental, although not of central importance or novelty, to evaluate the role carried out by brand trust and brand affect in the current study, as these more established factors are both recognised and valued by brands. For example, Heinz in their 2012 Annual Report regarded themselves as a globally trusted brand. In the current study, in confirmation with previous research (e.g. Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001), and hypotheses made, positive correlations were found between both brand trust and brand loyalty, and brand affect and brand loyalty. Whilst age of exposure significantly predicted brand loyalty for the tomato ketchup product, brand trust was a much stronger predictor, explaining 51% of the variance in brand loyalty. Additionally, unlike age of exposure, brand trust and brand affect were significant predictors of brand loyalty for the remaining six products; in each case brand trust was the strongest predictor.

One way in which the effects of brand trust and brand affect have been considered within consumer psychology is through parallels drawn from an understanding of human characteristics and relationships (e.g. Fournier, 1998; Davis, Buchanan-Oliver & Brodie, 2000; Sahin, Zehir, & Kitapçı, 2011). Fournier (1998) first proposed brand characteristics, and consumer-brand relationships could be understood this way. Committed partnerships, was one type of relationship Fournier (1998) suggested occur in both interpersonal relationships, and consumer-brand relationships; characterised by their long duration, closeness and trust. Sung and Kim (2010) highlighted strong brand personality increases brand affect and brand trust, in turn increasing brand loyalty (Siguaw, Mattila & Austin, 1999). However, Sung and Kim (2010) found levels of brand affect and trust felt by consumers varied across products when the factors were associated to personality dimensions. For example, the level of brand affect was more influenced than brand trust for a perfume product. It was postulated this might be due to the nature of the product and its related brands; a perfume could be considered as a product used to increase positive emotions, and therefore perfume brands might be associated to affective based personality dimensions (Sung & Kim, 2010). In accordance with this understanding, it could be suggested that the reason for brand trust being more strongly correlated and predictive of brand loyalty in the current study is due to the product categories used and their associated personality dimensions. Nevertheless, criticism has arisen regarding the implications of understanding brand-consumer relationships in the same way as interpersonal relationships, and brand characteristics alike to human characteristics (e.g. Bengtsson, 2003). Moreover, generalisations made upon the findings of studies of this nature (e.g. Fournier, 1998; Ji, 2002), should be made with caution; whilst they provide an in depth source of information they are based on limited interviews. Additionally, the importance of brand affect should not be discounted, as brand trust is not always shown to be the more predictive of brand loyalty. Various studies, for example Halim (2006), found the contrary. Also, Delgado-Ballester et al., (2003) criticised the definition of brand trust used by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) and consequently the definition of brand trust used in the current study. They suggest the constructs used by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) to test brand trust fall short of assuring psychological measurement.

It should be underlined that previous studies (e.g. Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2002; Matzler, Bidmon & Grabner-Kräuter, 2006) exploring the 28 role of brand trust and brand affect have differentiated products as being either hedonic or utilitarian, and have used these as control variables. Hedonic value was defined by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), as a product’s ability to create pleasure, whereas, utilitarian value was defined as a product’s capability to carry out its proposed function. Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001, 2002) highlight brand trust tends to be stronger if the utilitarian value of the product is greater, while products high in hedonic value are more likely to instil greater brand affect. As the products used in the current study were all under one overarching product category; food, products were not differentiated as being hedonic or utilitarian. This provides one possible explanation as to why differences in the levels of brand trust and brand affect in predicting brand loyalty were found.

Utilising Childhood Memories to Understand Brand Loyalty

As highlighted previously, the majority of participants stated their earliest memory with food was before their earliest memory with a branded product. From knowledge obtained from Morrison and Conway’s (2010) study, this is not surprising; it is unlikely participants acquired vocabulary relating to brands before they acquired vocabulary relating to food. Until individuals have acquired the vocabulary that explains an event, it is unlikely memories surrounding the event will be encoded, and thus retrieved in years to come (e.g. Morrison & Conway, 2010; Gross, Jack, Davis & Hayne, 2012). Therefore, the age of an individual’s first memory with a specific branded product would be predicted to be later than one with food.

Utilising individuals’ earliest childhood memories as a means of understanding current brand affiliations is a well-established technique (e.g. Hayne, 2004; Braun et al., 2002; Braun-LaTour et al., 2007; LaTour et al., 2010). However, the current study used this technique in a more indirect way, by asking participants for their earliest memories of each food product, as opposed to specifically asking for their earliest memory relating to the brand selected that they currently feel most loyal towards. For example, participants were asked to recall their earliest memory from the product cue word, ‘tea’, as opposed to their earliest memory from a brand cue; ‘PG tips’. This method, has allowed for particular importance to be placed upon the brands that were mentioned in participants’ earliest memories of food, recalled as part of their autobiographical memory years later; Walkers, Heinz, Marmite, Nutella, Dairylea, Lucozade, McDonalds and Walls. Ji (2002) 29 underlined the ability of an individual to be able to recall a specific brand name as part of their earliest memory of an interaction with a product, is a significant indication the individual formed a meaningful relationship with that brand as a child.

This meaningful relationship is something brands undoubtedly strive to achieve; brands certainly recognise the significance and importance of being part of their consumers’ autobiographical memories. For example; Heinz, a brand recalled at high frequency in the current study by participants in their earliest memories of food, ran a competition in the United States in 2009; ‘Heinz Wholesome Memories’, whereby individuals were required to send in their memories with Heinz tomato ketchup product. The importance of brand memories, clearly recognised by Heinz, might explain its particular prominence in the current study. Additionally, it has been acknowledged brands use autobiographical advertisements to generate nostalgia felt by a consumer (Braun et al., 2002). Braun et al., (2002) highlighted the use of autobiographical advertisements influenced individuals to believe their childhood experiences mirrored what they were exposed to in advertisements. This finding questions whether participants in the current study were easily able to distinguish between memories truly representing their childhood experiences with food brands, and brand advertisements they have subsequently been exposed to (e.g. Braun et al., 2002; Braun-LaTour, LaTour, Pickrell & Loftus, 2004; Braun-LaTour & Zaltman, 2006). Similarly, a question frequently disputed in autobiographical memory literature is whether an individual’s recollected memories of childhood solely represent what they can personally recall, or if their memories are embedded with subsequent information from family members or photographs (e.g. Garry & Gerrie, 2005). This was recognised prior to the current study, therefore to minimise these effects, unlike previous research (e.g. Lupton, 1994; LaTour et al., 2007; LaTour et al., 2010), participants were not informed prior to the questionnaire that they would be asked to recall memories from their childhood. Nevertheless, it cannot be guaranteed the childhood memories of food products recalled by participants were not contaminated by subsequent informational input. Equally, the age at which memories occurred and the accuracy of each memory was a subjective measure provided by participants.

It is necessary to briefly discuss the nature of participants’ earliest memories. In line with findings from Lupton’s (1994) seminal study, words used of highest frequency in participants’ memories from the current study can be broadly characterised and related to 30 familial relationships and environments, supporting research that emphasises the importance of exploring earliest memories as a means of understanding close interpersonal relationships (e.g. Mosak & Di Pietro, 2006). As mealtimes are a central part of a child’s upbringing in Western societies (LaTour et al., 2010), it is not surprising prominent individuals, primarily caregivers, were frequently recalled in participants’ earliest memories of food.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Whilst the current study only found a significant relationship between age of exposure and brand loyalty for one of the products; tomato ketchup, there are several limitations that need to be addressed before the role of early exposure is discounted. It should be noted in general participants did not score highly on measures of brand loyalty, brand affect and brand trust; several factors might be accountable for this. Firstly, the questionnaire was online and therefore completed in an uncontrolled environment. LaDoux (1996) underlined autobiographical memories are more likely to be accessible when individuals are in a calm state of mind. However, the current study had no control or knowledge of participants’ mood state. Additionally, no knowledge of how much attention participants gave to the questionnaire was available. Equally, although a pilot study was conducted to test the validity of the questions used, participants might have interpreted the questions in a different way to that intended. Moreover, it is disputed in consumer psychology literature as to whether an accurate measure of brand loyalty exists; it is argued although interest in the area has grown, there has not been a vast improvement in the accuracy of measurement (Zehir, et al., 2011). Future research should work on improving brand loyalty measurement to more accurately explore its relationship with early exposure. Likewise, it would be beneficial to explore the relationship on a wider range of food products.

Although the current study found significant correlations between predictor and outcome variables, due to the correlation design adopted, the direction of causality cannot be inferred. For example, it cannot be assumed early exposure to tomato ketchup caused brand loyalty to increase or vice versa; this highlights a central limitation of the study. Future research aiming to explore brand loyalty, could build upon previous correlational research by incorporating the use of neuroscience (Plassmann et al., 2012). It is 31 postulated that neuroscience techniques and methodologies will offer an innovative understanding of the psychological underpinnings of brand loyalty by going beyond conscious awareness. Thereby providing an implicit measure of brand memory, which reduces the subjectivity of recalled brand memories and subsequent brand loyalty scores (e.g. Plassmann et al., 2012; Nevid, 2010). This might also reduce the impact of false brand memories, which can be caused by exposure to advertising.

Moreover, as shown in regression analysis the three predictor variables age of exposure, brand trust and brand affect did not account for all of the variance in brand loyalty. Accordingly, it cannot be concluded there are no further variables that cause brand loyalty; other unexamined variables must explain the remaining variance. Additionally, generalisations made based upon the findings from this study which demonstrated brand trust was more strongly correlated, and a better predictor of brand loyalty, should be made with caution. Although this was found for each of the seven products tested, the mediating role of the utilitarian or hedonic value of each product was not controlled. It has been previously found brand trust is more strongly associated with utilitarian products (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2002), therefore, it must be acknowledged that brand trust may be the best predictor of brand loyalty for the products in the current study due to their high utilitarian value. Consequently, future research should control for this by determining the hedonic and utilitarian value of each food product (e.g. Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001, 2002; Matzler et al., 2006).

Whilst the basic nature of participants’ earliest food and brand memories were explored, it would be beneficial for future research interested in the significance of early exposure to branding to further explore the emotionality of memories recalled by participants; more emotionally salient brand memories are likely to have a greater influence on current brand loyalties (Bruhn, 1985). This would be impractical to explore with the sample size used in this study; however, future research could achieve this through interview methodology. Examining fewer participants would allow for a longitudinal study, permitting the impact of early exposure to be explored over a longer period. It might be found that an individual’s brand loyalty score varies as a function of time since initial exposure; the relationship between age of exposure and brand loyalty could be compared across an individual’s lifespan. The influence of early exposure on brand loyalty may be more pronounced at a young age; children and adolescence may show brand loyalties for 32 certain brands they have been exposed to as a consequence of not being financially independent. Therefore, it would be of interest to explore if an individual’s brand loyalty scores differ when they are at University for example; more financially independent and making brand purchases of their own, as is likely the case for the majority of participants in the current study. Nevertheless, generalisations based upon findings from fewer participants should be made with caution. Equally, as the current study did not take into account participants’ nationality, it would be of interest to explore the relationship between early exposure and brand loyalty cross-culturally. It has been previously suggested that an individual’s cultural values have an impact on their brand memories, and subsequently factors influencing brand loyalties (e.g. Lam & Lee, 2005; Seock & Lin, 2011).

Conclusion

From the findings of this exploratory study it can be concluded that the role of early exposure in ensuring brand loyalty is weaker than brand trust and brand affect. Although the findings do not provide a significant step towards placing early exposure in high regard, due to the limitations of the study outlined, it is important the role of early exposure is not dismissed prior to further research. As brand loyalty has recently been found to be regarded with less importance to individuals in Westernised countries (Ernst & Young, 2009), it is predicted the factors that determine brand loyalty will increasingly be explored and of interest to brands. Future research should endeavour to investigate if the role of early exposure is more significant when taking an implicit, objective measure of age of exposure and brand loyalty. Brand affect, although found to be a stronger predictor of brand loyalty than age of exposure, should be further investigated as it frequently receives less attention than brand trust. Utilising participants’ earliest memories of food provided a useful insight to determine if branding was of significance to individuals at a young age. This projective method should be utilised more effectively in future by studying fewer participants, thereby allowing the content of participants’ memories to be explored in greater detail. The rich contextual information collected will be invaluable to developing brand loyalty, as companies continually strive to be a significant part of their consumers’ lives.

References

Adler, A. (1937). The significance of early recollections. International Journal of Individual Psychology, 3, 283-287.

American Psychological Association. (1997). International Market Research Consultant. [Press release]. Retrieved March 19, 2013, from http://www.apa.org/careers/resources/profiles/garfein.aspx

American Psychological Association. (2000). Advertising to children: Is it ethical? Retrieved March 26, 2013, from http://www.apa.org/monitor/sep00/advertising.aspx

Auty, S., & Lewis, C. (2004). Exploring children’s choice: The reminder effect of product placement. Psychology & Marketing, 21(9), 697-713.

Bakir, A., & Vitell, S. J. (2010). The ethics of food advertising targeted toward children: Parental viewpoint. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 299-311.

Baloglu, S. (2002). Dimensions of customer loyalty: separating friends from well wishers. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43(1), 47-59.

Bengtsson, A. (2003). Towards a critique of brand relationships. Advances in Consumer Research, 30, 154-154.

Braun, K. A., Ellis, R., & Loftus, E. F. (2002). Make my memory: How advertising can change our memories of the past. Psychology & Marketing, 19(1), 1-23. Braun-LaTour, K. A., & LaTour, M. S. (2007).

Using Childhood Memory Elicitation to Gain Insights into a Brand at a Crossroads The In-N-Out Burger Situation. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 48(3), 246-273. Braun-LaTour, K. A., LaTour, M. S., Pickrell, J. E., & Loftus, E. F. (2004).

How and when advertising can influence memory for consumer experience. Journal of Advertising, 33(4), 7-25.

Braun-LaTour, K. A., LaTour, M. S., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2007). Using childhood memories to gain insight into brand meaning. Journal of Marketing, 71(2), 45-60.

Braun-LaTour, K. A., & Zaltman, G. (2006). Memory change: An intimate measure of persuasion. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(1), 57–72. Bruhn, A. R. (1985).

Using early memories as a projective technique-The Cognitive Perceptual method. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(6), 587-597. Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001).

The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. The Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81-93. Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2002).

Product-class effects on brand commitment and brand outcomes: The role of brand trust and brand affect. The Journal of Brand Management, 10(1), 33-58. Chernin, A. (2008).

The effects of food marketing on children’s preferences: testing the moderating roles of age and gender. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 615(1), 101-118. Conway, M. A., & Rubin, D. C. (1993).

The structure of autobiographical memory. In A.E. Collins, S. E. Gathercole, M. A. Conway, & P. E. Morris (Eds.), Theories of Memory (pp. 103-137).

Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Davis, R., Buchanan-Oliver, M., & Brodie, R. J. (2000).

Retail service branding in electronic-commerce environments. Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 178-186. de Chernatony, L., & McDonald, M. (1992).

Creating powerful brands (2nd Ed.) Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Delgado-Ballester, E., Munuera-Aleman, J. L., & Yague-Guillen, M. J. (2003).

Development and validation of a brand trust scale. International Journal of Market Research, 45(1), 35-54. Ernst & Young. (2012).

MENA Customer barometer: This Time its personal: from consumer to co-creator [Brochure]. Retrieved April 2, 2013, from http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/MENA_Customer_Barometer_July_2012/$ File/2012%20MENA%20Customer%20Barometer%20v23.pdf Evanschitzky, H., Iyer, G. R., Plassmann, H., Niessing, J., & Meffert, H. (2006).

The relative strength of affective commitment in securing loyalty in service relationships. Journal of Business Research, 59(12), 1207-1213.

Facebook Newsroom. (2013). Investor Relations [Fact sheet]. Retrieved March 19, 2013, from http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=736911 Fournier, S. (1998).

Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 343-353. Freud, S. (1899).

The standard edition of the complete works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press. Garry, M., & Gerrie, M. P. (2005). When photographs create false memories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(6), 321-325. Gecti, F., & Zengin, H. (2013).

The Relationship between Brand Trust, Brand Affect, Attitudinal Loyalty and Behavioral Loyalty: A Field Study towards Sports Shoe Consumers in Turkey. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 5(2), 111-119. Goldberg, M. E., Gorn, G. J., & Gibson, W. (1978).

TV messages for snack and breakfast foods: do they influence children’s preferences?. Journal of Consumer Research, 5(2), 73- 81. 36 Gross, J., Jack, F., Davis, N., & Hayne, H. (2012). Do children recall the birth of a younger sibling? Implications for the study of childhood amnesia. Memory, 1-11. Guest, L. (1964). Brand loyalty revisited: A twenty-year report. Journal of Applied Psychology, 48, 93–97.

Halim, R.E. (2006). The Effect of the Relationship of Brand Trust and Brand Affect on Brand Performance: An Analysis from Brand Loyalty Perspective (A Case of Instant Coffee Product in Indonesia), 1-14. doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.925169

Hayne, H. (2004). Infant memory development: Implications for childhood amnesia. Developmental Review, 24(1), 33-73. Heinz. (2009).

Heinz® Ketchup and Josie Bissett Team up to Grow 57,000 Wholesome Memories [Press release]. Retrieved March 25, 2013, from http://www.heinz.com/ourcompany/press-room/press-releases/press release.aspx?ndmconfigid=1012072&newsid=20090707005822

Heinz Annual Report. (2012). Growing Ketchup Globally. Retrieved March 13, 2013, from http://www.heinz.com/AR_2012/Heinz_Annual_Report_2012.pdf

Jack, F., & Hayne, H. (2007). Eliciting adults’ earliest memories: Does it matter how we ask the question?. Memory, 15(6), 647-663.

Jack, F., & Hayne, H. (2010). Childhood amnesia: Empirical evidence for a two-stage phenomenon. Memory, 18(8), 831-844.

Janiszewski, C. (1993). Preattentive mere exposure effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 376-392.

Ji, M. F. (2002). Children’s relationships with brands: “True love” or “one‐night” stand?. Psychology and Marketing, 19(4), 369-387.

John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twentyfive years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26(3), 183-213.

Josselson, R. (2000). Stability and change in early memories over 22 years: Themes, variations, and cadenzas. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 64(4), 462-481.

Josselyn, S. A., & Frankland, P. W. (2012). Infantile amnesia: A neurogenic hypothesis. Learning & Memory, 19(9), 423-433. Kingo, O. S., Berntsen, D., & Krøjgaard, P. (2013). Adults’ Earliest Memories as a Function of Age, Gender, and Education in a Large Stratified Sample. Psychology and Aging. Advance Online Publication. doi:10.1037/a0031356

Kotler, P. (1972). A generic concept of marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 36, 46-54.

Kunkel, D., Wilcox, B., Cantor, J., Palmer, E., Linn, S., & Dowrick, P. (2004). Psychological issues in the increasing commercialization of childhood. Report of the APA Task Force on Advertising and Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lam, D., & Lee, A. Y. (2005). The influence of cultural values on brand loyalty. ANZMAC: Proceedings of the Australia and New Zealand Marketing Association Conference 2005: Broadening the Boundaries, 163-171.

Laroche, M., Habibi, M. R., & Richard, M. O. (2013). To be or not to be in social media: How brand loyalty is affected by social media? International Journal of Information Management, 33(1), 76-82.

LaTour, K., LaTour, M. S., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2010). Coke is It: How stories in childhood memories illuminate an icon. Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 328-336.

LeDoux, J. E. (1996), The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Lupton, D. (1994). Food, memory and meaning: the symbolic and social nature of food events. The Sociological Review, 42(4), 664-685.

MacDonald, S., Uesiliana, K., & Hayne, H. (2000). Cross-cultural and gender differences in childhood amnesia. Memory, 8(6), 365-376.

Matzler, K., Bidmon, S., & Grabner-Kräuter, S. (2006). Individual determinants of brand affect: the role of the personality traits of extraversion and openness to experience. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(7), 427-434.

Miles, C. (1893). A study of individual psychology. American Journal of Psychology, 6, 534- 558.

Morrison, C. M., & Conway, M. A. (2010). First words and first memories. Cognition, 116(1), 23-32.

Mosak, H. H., & Di Pietro, R. (2006). Early recollections: Interpretive method and application. Abingdon: Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Mullen, M. K. (1994). Earliest recollections of childhood: A demographic analysis. Cognition, 52(1), 55-79.

Nevid, J. S. (2010). Introduction to the special issue: Implicit measures of consumer response—The search for the holy grail of marketing research. Psychology & Marketing, 27(10), 913-920.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Olenski, S. (2012). Only One Quarter Of American Consumers Are Brand Loyal. Retrieved March 29, 2013, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/marketshare/2012/03/26/only-one-quarter-of-americanconsumers-are-brand-loyal/

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33-44.

Pepper, M., Jackson, T., & Uzzell, D. (2009). An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviours. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(2), 126-136.

Peterson, C., Grant, V., & Boland, L. (2005). Childhood amnesia in children and adolescents: Their earliest memories. Memory, 13(6), 622-637.