How do you want to be remembered? It’s a question humans have asked since time began, but have you ever paused to think about it – I mean really think about it? Who do you want to be remembered as, which stories do you want your grandchildren to hear? When you’re dead and gone and no longer able to put it in your own words, who will decide your ‘legacy’? For some, with cash and time to spare, the answer to that question is “through my own professionally-written autobiography” – and it’s leatherbound. Welcome to the age of the memoir, where everybody is a main character.

I’m on my way to meet Roy Moëd. He first made his fortune selling juice ‘cuplets’ to airlines but now operates in the far more intangible world of storytelling. His business Lifebook Memoirs is – in short – a service that will write you your own autobiography. Equipped with interviewers, ghostwriters, editors and an all-the-frills production team, Lifebook promises to take your story, no matter how banal or ordinary, and distil it into a polished 200-or-so-page memoir that you can place on the shelf for posterity. And you don’t have to write a word.

I approached Moëd for a quick chat over the phone about how this kind of service works, but a phone call isn’t quite Moëd’s style. Instead, I find myself on a train to leafy Godalming, where Moëd has offered to show me around Lifebook’s HQ.

Rolling into the station around midday (to ensure we have “plenty of daylight”), I’m awaited by Moëd in a vintage, midnight blue Citroën 2CV. “You won’t miss my car,” he had told me in advance. A short trundle down prime stockbroker belt country lanes later and we pull up at the kind of house that can only suggest business is doing well (stables, lush gardens and a 17th century barn converted not only into a space for Lifebook’s office but also an indoor pool).

I’m ushered into the home office, where the faces of Lifebook’s 12,000 memoirists beam at me from the booklined walls. I settle into one of two armchairs set up in front of a spaceship-looking modern fireplace and tuck into a platter of sushi that had been prepared ahead of my visit. When Moëd tells me he values creating an experience, I believe him.

Lifebook is just one company offering “private autobiographical services”, an industry which seems to have sprung up overnight. The pandemic, which encouraged many to take stock of their own lives while also confronting us with our own mortality, has certainly played a part in their success – but it’s not the whole picture. Services range in price (and corresponding paper quality), but you can expect to pay at least £1,000 (and even that’s the cheapskate’s choice and may involve your ‘ghostwriter’ being an AI bot). Lifebook, by contrast, is unashamedly on the indulgent end. Their process is lengthy and expensive, taking around six to 12 months and £12,000 to complete. Interviewers are hand-selected by project, and chosen only if they live within a 30 minute drive of the subject, who they will be visiting for around a dozen 90-minute sessions in order to extract all their best anecdotes to then be sent onto a ghostwriter to thread into a narrative.

•••

The average age of a Lifebook customer is 80, but first on my list is Haviva, ‘lead of employability programs’ at Google, who had her memoir written at just 40 years old. Haviva had always said she would write a book, but it was her husband who pushed her when he bought her the Lifebook experience for her birthday. When I went to meet her, I was expecting a Steven Bartlett-style discussion about the grind and the hustle but Haviva turns out to be far less concerned about herself than someone who has written a memoir at 40 would suggest. On the contrary, I find myself answering more questions about myself than asking them of her as we shoot up in the glass elevator to chat over coffee on the top floor of Google’s King’s Cross office.

Haviva is explicit though: she always wanted to be special. “One of the things that really became clear to me, and this was from a young age, is that I had a disdain for averageness. It’s a really deep-seated sentiment. I can’t deal with the mundane. I’ve always struggled in an average setting.”

Growing up in a community in Los Angeles where nobody really went to college, Haviva said she had a chip on her shoulder. She left home at 12 so she could attend a school where she won a scholarship, working in exchange for room and board with local families. In her memoir, this chapter is called ‘Cinderella’.

People want to know that their lives have meaning, that their little speck of time, 70 years, 80 years on this earth, has some value

Studying in Ghana, moving to Tanzania, the time she met Bashir al Assad, being in a grenade attack – Haviva has an adventurous and turbulent life. What becomes clear, though, is that far from just documenting it, Haviva’s memoir was a way to reckon with it. “I wanted to put my past behind me.” It was akin to therapy.

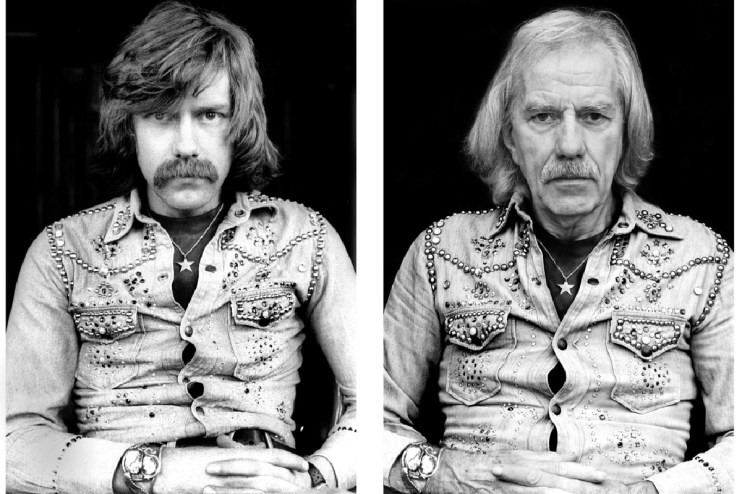

Nigel, a 79-year-old retiree, is less sugary. His book stood out on the shelf when I visited Roy: on the front, a picture of Nigel, clad in a denim shirt, in his moustachioed prime. On the back, a picture-perfect recreation, now aged in his seventies. He certainly looks like a main character.

Nigel is far briefer on his motivation to write a memoir: “I heard my daughter telling my stories and getting them wrong.” He pauses. “And, I suppose, I wanted to show off a bit really.” I appreciate his honesty.

He tells me about his free-spirited life as a photographer in the 1970s, hanging around Carnaby Street and living la vie bohème. He lived among the kind of crowd good for anecdotes, once even going to the pictures with Princess Margaret.

I ask if the process of writing his memoir helped him reframe his life, or come to any epiphanies, but Nigel says I’m getting carried away. “I don’t think it gets that deep,” he says. “I just thought it would be nice for my daughter.” I change tack and ask if it’s achieved his objective: does his daughter now get his stories right? “I don’t think she read it in depth,” he says.

•••

When looking at the rise of memoir-writing, “democratisation” is a key theme. “This is the age of memoir,” William Zinnser declared in the 1980s. In the 1990s, he doubled down: “Never have personal narratives gushed so profusely from the American soil… Everyone has a story to tell, and everyone is telling it.” He was referring to the rise of what some have dubbed the “nobody memoir”, stories written by ordinary people about ordinary lives. Author of The Liars’ Club Mary Karr, whose memoir about growing up in Texas with two alcoholic parents has been widely credited for launching a resurgence in these books of this kind in the 1990s, says it’s exactly this that she loves about the genre: “Its democratic (some say ghetto-ass primitive), anybody-who’s-lived-can-write-one aspect”.

Since then, the genre has only gathered pace. According to Goodreads, 443 memoirs were published in English in 2023, up from 108 in 2019. In the age of the selfie, it’s hardly a surprise this me-centric narrative has gained traction. Companies inserting your child’s name into children’s books to make them the main character is just another symptom of this age. Today’s rent-a-memoirist services hardly advertise themselves as providers of the “nobody memoir”, but there is certainly a lineage. “Everyone’s got a story, and everyone’s story is valuable,” Nick Boulos, the founder of another memoir-writing service, Master Storytellers, says. “We have clients for whom it’s been bought as a gift, who say ‘I’ve not done anything and I’ve just been a housewife blah blah blah.’ But they’ve definitely done more or achieved more than they think they have.”

Not every memoirist I spoke to thought this way. “With no disrespect, if you sort of grew up normally, worked on a bus all your life, done nothing, then you’ve got no content,” says Lifebook customer Jimmy, an East Londoner who heads up a fruit and veg business. “I don’t know anybody who’s done more than I’ve done. That sounds terribly arrogant but it’s not like that.” Lifebook’s standard packages come with 12-24 physical copies of your book included, but Jimmy tells me he’s already given out 150.

•••

When I ask Moëd why he thinks people want their memoirs written, he describes it simply. “They want to know their lives have meaning, that their little speck of time, 70 years, 80 years on this earth, has some meaning.”

His own inspiration for the company was personal, and maybe also regretful. Wanting to find an occupation for his father, almost blind and battling depression, he started sending his secretary to go visit him, ask him about his life and record the stories. Moëd had already heard them all.

It was only after his father died that he compiled them and found there were stories he had never heard. “And I couldn’t ask him about them anymore.” Moëd admits he’d often shut down his father’s storytelling; his secretary, by contrast, a stranger (and on paid time), would ask him what happened next. Having strangers conduct the interviews for his clients now is a key tenet of the approach.

Many, in writing their memoirs, are confronting death. One woman I spoke to had used Boulos’s service to write her younger brother’s memoir after he tragically died of cancer after a diagnosis at 19. The memoir was written after his death, pieced together from interviews with her, his doctors and others in his life, but written in ‘his’ voice. In a similar vein, Master Storytellers recently set up a sister non-profit endeavour, The Storytellers Foundation, which writes memoirs for the terminally ill as a way for them to live on.

Many, in writing their memoirs, are confronting death. One woman I spoke to had used theservice to write her younger brother’s memoir after he died of cancer after a diagnosis at 19

Moëd tells me about another of his clients, a woman with no family left who was living in a care home. She was scared of being forgotten. Moëd says he was concerned about taking her money, but she was resolute. “I’ve got no one to leave my money to. I want this. This is my legacy.” She wrote her memoir and gave a copy to every member of the care home staff and some of the residents. In the front is a dedication to St Leonard’s taxi company, which drove her to church every Sunday.

Gesturing at the shelves, Moëd says what he has, really, is an amazing resource of social history. I’m reminded of a summer I’d spent in the office of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) as an intern, where piles and piles of huge leatherbound books fill the room, containing thousands of biographies of “notable” people. The ODNB is a ‘great man’ enterprise, but its sheer size is humbling – even those who make it are just one of many. “The very act of putting someone in a collection of biographies cuts people down to size,” says Dr Alex May, the Dictionary’s senior researcher.

Perhaps the modern impulse for memoir-writing, then, does the opposite: expands the everyman into the great man. Or, perhaps more accurately, allows them to view themselves as such.

One memoirist’s daughter got in touch with Moëd after reading her mother’s book. “I hope you know, not a word of that memoir is true!” she told him. But Moëd says that didn’t matter. As Zinnser puts it: memoir is the art of inventing the truth. No wonder it’s booming.

• Read more of City AM The Magazine here